Exclusive: Pakistan’s nuclear arsenal remains a top global security threat, as Islamic jihadists penetrate many of the nation’s political, educational and military institutions, says Jonathan Marshall.

By Jonathan Marshall

Dozens of world leaders are arriving in Washington, D. C. for the fourth Nuclear Security Summit, a biennial event dedicated to minimizing the threat of loose nuclear material falling into the hands of terrorists or rogue nations.

The summit couldn’t be more timely in view of recent revelations that militants linked to the Islamic State recruited two employees at a Belgian nuclear plant where an insider in 2014 drained thousands of gallons of lubricating oil, severely damaging its turbines.

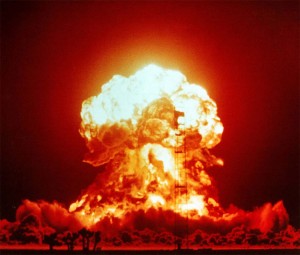

A nuclear test detonation carried out in Nevada on April 18, 1953.

The summit also comes just days after North Korea released a video threatening a nuclear first strike against Washington — an unrealistic but unsettling boast from one of the world’s most repressive and impenetrable regimes.

But an even greater threat to nuclear security lies thousands of miles from Belgium and Korea — in Pakistan. It is home to about 120 atomic weapons, making it the world’s fifth largest and fastest growing nuclear arsenal. Pakistan also has large stockpiles of highly enriched uranium and plutonium for making dozens of new warheads.

No one should sleep well while the armed forces who are responsible for securing that deadly stockpile continue to collaborate openly with armed extremists at home and abroad, and adopt provocative doctrines for using nuclear weapons on the battlefield.

Pakistan is one of the last places on Earth to which you’d want to entrust nuclear weapons. The Pakistani industrialist Shakir Lakhani last year declared his country a “failed state,” noting that corruption is rampant and that terrorists “have infiltrated our institutions, our schools and colleges, our universities, our police departments, our armed forces and perhaps even our judiciary.”

The celebrated journalist Ahmed Rashid warns that Pakistan is “in the process of dissolution, facing the same fate as Syria or Somalia.”

Government collapse in Pakistan is the private worry of every nuclear security planner today. Said Gary Sanmore, former National Security Council Coordinator for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation, “as we look at the sectarian violence and tensions between the government and the military and so forth — I worry that . . . even the best nuclear security measures might break down. You’re dealing with a country that is under tremendous stress internally and externally, and that’s what makes me worry.”

In words that remain as plausible as ever today, the noted American arms control expert Robert Gallucci said a decade ago that Pakistan is “the number one threat to the world … [I]f it all goes off — a nuclear bomb in a U.S. or European city — I’m sure we will find ourselves looking in Pakistan’s direction.”

The Terrorist Threat

Although Pakistan’s atomic weapons are doubtless well protected, they remain highly vulnerable to insiders motivated either by extremist ideology or corrupt inducements — both of which are in ample supply. Pakistan makes matters worse by bolstering and in some cases creating the very terrorists who threaten its nuclear stockpiles.

Pakistan has long been a sponsor of international terrorism, most notably in Afghanistan and especially India, its hated enemy. For example, Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) agency helped spawn the notorious group Lashkar-e-Taiba to fight Indian forces in Kashmir.

Terrorist attacks on India’s parliament in 2001 and Mumbai in 2008 were spectacular outcomes of Pakistan’s malign policy. Pakistani leaders apparently also sheltered Osama bin Laden until the U.S. Navy SEAL raid in 2011, according to a former defense minister.

Days after the leaders of India and Pakistan met on Christmas Day last year in Lahore, terrorists from Pakistan attacked a major Indian airbase, preventing a thaw in the two country’s relations. That attack may have been independently planned, but Pakistan’s military and intelligence services have a long history of sponsoring such terrorist provocations to derail peace initiatives.

According to Christine Fair, an associate professor at Georgetown University, “Pakistan’s security institutions have instrumentalized a menagerie of Islamist militants to prosecute its internal as well as external policies with respect to India and Afghanistan.

“Since 2001, many of these erstwhile proxies have turned their guns and suicide devices on the state and its citizenry under the banner of the Pakistani Taliban. A lack of both will and capacity hinder the state’s ability to effectively confront this threat and secure its population.

“Most problematically, Pakistan still wants to nurture some militants who are its assets while eliminating those who fight the state. Civilians lack the ability, will, or vision to force the security forces to change tactics.”

The resulting “blowback” from Pakistan’s support of terrorism has taken a huge toll, like the suicide bombing in Lahore this Easter. Although it received less media attention than the recent terrorist attacks in Brussels, the Lahore bombing a killed twice as many victims.

From 2002 to 2011, terrorists in Pakistan killed 3,700 people and wounded another 9,000. Several times that number died from other forms of political, ethnic, communal, and Islamist violence.

The attack in Lahore was carried out by a break-away faction of the government-sponsored Pakistani Taliban. Gunmen from the Pakistani Taliban previously killed 22 people at Bacha Khan University in January and 145 people, mostly children, at a school in Peshawar last year. The government has been unable or unwilling to rein in such extremist violence. Someday it may prove equally unable to rein in terrorist attacks on its nuclear installations.

The Obama administration knows this, but for the most part maintains the fiction that Pakistan’s military has its nuclear arsenal fully under control. One reason for its diplomatic language and continued military aid is to avoid a rupture that would jeopardize continued U.S. military operations in Afghanistan (as almost happened in 2012 after Pakistan closed NATO supply routes following American airstrikes on Pakistani soldiers suspected of aiding the Taliban).

Privately, however, President Obama “questions why Pakistan, which he believes is a disastrously dysfunctional country, should be considered an ally of the U.S. at all,” reports Atlantic magazine’s Jeffrey Goldberg.

President Barack Obama shakes hands with U.S. troops at Bagram Airfield in Bagram, Afghanistan, Sunday, May 25, 2014. (Official White House Photo by Pete Souza)

According to David Sanger, Obama told his staff in 2011 that Pakistan’s potential disintegration — and the resulting “scramble for its (nuclear) weapons” — represented his “single biggest national security concern.”

A Question of Doctrine

In addition to having “the world’s fastest-growing nuclear arsenal,” Pakistan “is shifting toward tactical nuclear weapons intended to be dispersed to front-line forces early in a crisis, increasing the risks of nuclear theft should such a crisis occur,” according to a new report on “Preventing Nuclear Terrorism” by experts at Harvard University’s Belfer Center.

Pakistan intends to use these smaller nuclear warheads against conventional Indian forces in case another war breaks out between the two major powers on the Asian subcontinent. Such mobile weapons are inherently vulnerable to seizure by terrorists during transit.

The intended tactical use of such weapons on the battlefield also raises the odds of any military conflict escalating rapidly to an all-out nuclear war. During a war over Kashmir in 1999, Pakistan’s government “ordered the arming of its nuclear missiles, potentially bringing the two countries to the brink of a nuclear conflict,” according to military historian Joseph Micallef.

Needless to say, an all-out nuclear war between India and Pakistan could kill, wound or sicken tens of millions of people and render much of South Asia virtually uninhabitable.

“We are really quite concerned about . . . the destabilizing aspects of their battlefield nuclear weapons program,” said the U.S. Undersecretary of State for Arms Control and International Security Rose Gottemoeller in testimony before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee this March. To which a senior Pakistani nuclear adviser replied, “We are not apologetic about the development of [tactical nuclear weapons] and they are here to stay.”

Washington’s Inadequate Response

The Obama administration recognizes the threat from Pakistan and other source of “loose nukes” but has failed to make them a priority. As Steve Mufson reported in the Washington Post, “in his fiscal 2017 budget, Obama has proposed deep cuts in spending on programs to stop nuclear proliferation while leaving intact military spending on a new generation of weapons. . . .

“For fiscal 2017, the Obama administration has proposed its smallest nuclear security budget ever. The proposal would slash spending for the National Nuclear Security Administration’s international program by roughly two-thirds, to a level last seen in the mid-1990s.”

Besides restoring funding, the administration should make collaboration with Russia on nuclear security programs a higher priority than escalating conflicts over less vital issues like the future of Crimea.

In a letter sent to President Obama on March 28, six Democratic U.S. senators also recommended that his administration lead by example, and seek to reduce the bloated nuclear arsenals of the United States and Russia to 1,000 warheads and 500 delivery vehicles by 2021.

With regard to Pakistan, Washington should apply more pressure — including withholding military aid — to restrain its provocative nuclear policy toward India, and its support for terrorist organizations.

At the same time, however, the administration should avoid special favors to India that stoke Pakistan’s paranoia and resentment. For example, the Bush administration’s nuclear cooperation agreement with India, which allowed U.S. nuclear technology sales to India, contributed to the arms race between India and Pakistan and “did long-lasting damage toward both the global non-proliferation norms and the efforts to eliminate nuclear weapons,” according to Subrata Ghoshroy, a researcher at MIT.

And if Washington really wants to get serious about Pakistan, it must eliminate Islamabad’s remaining leverage over the United States. That means withdrawing U.S. forces from Afghanistan once and for all, so Pakistan cannot unleash its proxies to kill American soldiers or cripple the U.S. logistics chains.

Once Afghanistan is off its agenda, Washington can finally focus on that region’s real threat to world security: Pakistan’s growing nuclear stockpile.

Jonathan Marshall is author or co-author of five books on international affairs, including The Lebanese Connection: Corruption, Civil War and the International Drug Traffic (Stanford University Press, 2012). Some of his previous articles for Consortiumnews were “Risky Blowback from Russian Sanctions”; “Neocons Want Regime Change in Iran”; “Saudi Cash Wins France’s Favor”; “The Saudis’ Hurt Feelings”; “Saudi Arabia’s Nuclear Bluster”; “The US Hand in the Syrian Mess”; and “Hidden Origins of Syria’s Civil War.” ]

Comments

Post a Comment